Sexual violence may be defined as sexual activity used with the purpose of manifesting aggression or causing physical harm or psychological damage to the subject of the attack. Rape is a particular type of sexual violence: a penetrative sexual assault. The term “mass rape” refers to the military strategy of widespread, systematic sexual violence and rape perpetrated intentionally against civilian women. In this analysis, living women who have been raped are referred to as survivors, while those who died are referred to as victims.

The UN Commission on Human Rights issued a document on the former Yugoslavia in which rape is classified as “an abuse of power and control in which the rapist seeks to humiliate, shame, embarrass, degrade, and terrify the victim (Falcon, 2001, p. 31). It identified the “exercise power and control over another person” as the primary objective of rape (Falcon, 2001, p. 31).

In the act of rape, the “perpetrator’s sexuality is not an end;” sexuality is an instrument to inflict damage through “sexual means” (Seifert, 1994). Some have argued that “rape is not an aggressive expression of sexuality, but a sexual expression of aggression… it is a manifestation of anger, violence, and domination of a woman. The purpose is to humiliate, degrade, and subjugate” (Seifert, 1994). Support for this assertion includes the fact that the physical violence associated with rape often far exceeds the level necessary to complete the sexual act and that rapists speak of the experience as an aggressive act of dominance, associated with power, rather than particularly sexual act (Heise, 1998). Rape may be used to regulate power relations between genders or between groups (Seifert, 1994).

It has been largely agreed that rape is an act of domination, yet “the violence of rape is peculiarly sexual” and differs contextually from a purely physical assault (Cahill, 2001, p. 27). The sexual nature of the violence may increase the impact of rape because of the cultural and social context, or personal and situational factors, in which the rape occurs and is understood (Cahill, 2001). While men can be raped, this work focuses on the experience of women raped during war as part of a strategy of cultural control.

SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM

It is difficult to quantify the prevalence of mass rape, or to determine with any validity the number impacted by sexual violence in these conflicts, because these women are war’s forgotten victims. Rape is still a stigmatized topic, so it is seriously underreported due to numerous practical and social factors. It is challenging to obtain an accurate census of any kind during a conflict or in active combat zones, and collecting data about sexual violence is wrought with difficulties. Regardless of this complexity, estimates show that scope of the problem of mass rape is appalling, especially considering the fact that most estimates do not account for the complete total. There may be many more survivors and victims than the world will ever know.

Modern war and genocide campaigns utilize mass rape as a strategy to leave vast numbers of severely traumatized victims in their wake (Parin, 1994; Turshen, 2000). Sexual violence and rape were present during WWI and prevalent during WWII. The Nazis are reported to have branded some women with the inscription “Whore for Hitler’s troops,” and it was common for persecuted women to be raped or sexually assaulted in concentration camps and elsewhere (Heise, 1998). The Tokyo Tribunal stated that the Japanese Army raped 20,000-80,000 women during the “Rape of Nanking” in 1937, and enslaved 100,000-200,000 “comfort women” who were forcibly imprisoned and raped to serve the soldier’s sexual needs during the war (Chang, 1997, p. 6). Soviet soldiers reportedly raped more than 2 million German women during the final stages of WWII, and hospital statistics indicate between 95,000 and 130,000 women were raped in Berlin alone. Other modern conflicts have featured mass rape, but it is difficult to obtain credible statistics documenting these atrocities. One well-documented crisis of mass rape occurred in Bangledesh in 1971: it is reported that 200,000 women were raped during conflicts that erupted that year (Heise, 1998).

An estimated 25,000 to 50,000 women were systematically raped during the Balkan Wars of the 1990s; it had been reported that up to 20,000 of these women were forcibly impregnated, and more than 5,000 “bad memory babies” were abandoned on hillsides or killed in the aftermath (Boose, 2002, p. 71; Hardy, 2001, p. 4). The 1994 Rwandan genocide left an estimated 250,000 to 500,000 rape survivors in a single summer, with more than 2,500 infants born the following spring and abandoned (Human Rights Watch, HRW, 1996). This continues to be a pressing issue as mass rape and genocide have recently been reported in the Darfur region of the Sudan by reputable organizations such as Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International and UNICEF (ICRC, 2005; OXFAM, 2006; PHR, 2006; UNICEF, 2006, 2007). It is unknown how many women may be at risk for experiencing mass rape, but these estimates reveal that the problem of mass rape impacts modern women at an alarming scale.

SEXUAL VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN:

AN ECOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK

Rape does not have constant functions over time and in all societies, because sexual violence is highly contextualized by individual, situational, social and cultural factors. It is important to contextualize the meaning and function of rape in terms of these social and cultural realities, as well as individual and situational factors that mediate the meaning and function of sexual violence. (Seifert, 1994). A nested, ecological framework of violence against women conceptualizes rape as a multi-faceted phenomenon grounded in an interplay among personal, situational, and sociocultural factors (Heise, 1998).

This ecological framework was developed from findings from a variety of fields, from research relating to all types of physical and sexual abuse of women (Heise, 1998). Because there is little consensus on the etiology of violence against women, it is important to build a model which can contain several explanations and levels of interaction and meaning (Heise, 1998). Only recently have theorists begun to conclude that a complete understanding of gender abuse may require acknowledging factors operating on multiple levels, and this framework encourages “a more integrated approach to theory regarding gender-based abuse” (Heise, 1998). A nested framework allows researchers to “grapple with real life,” by incorporating various perspectives and featuring multiple levels of meaning in the analysis (Heise, 1998, p. 285).

Embedded levels of causality are essential to the ecological framework of sexual violence against women (Heise, 1998, see Figure 1). Heise (1998) describes four levels of influence: individual/ontogenic factors, microsystem/situational factors, exosystem/social structure factors, and macrosystem/cultural factors. The ecological framework applied to the etiology and the consequences of sexual violence against women focuses on the salience of factors at a variety of levels of the social ecology, while attending to the combined influence and interplay between these factors. Acknowledging the influence of situational factors or personal history in no way exculpates the perpetrators of violence, nor does it reduce the salience of macro level factors, such as cultural notions of masculinity and male dominance over women. An comprehensive analysis of sexual violence must recognize the primacy of culturally constructed messages about masculinity/femininity and gender/power roles, while also accounting for social, situational, and individual factors (Heise, 1998).

Ontogenic factors are those features of an individual’s history, developmental experience, or personality that shape the way they respond to microsystem and exostsyem stressors, as well as macrosystem messages that they experience (Heise, 1998). Individual factors such as childhood experiences of abuse or violence, witnessing violence, and previous trauma have been associated with later sexual violence (as victims and perpetrators). Individual factors, such as upbringing, family of origin, genetics, previous experience, and other factors have been linked to resilience and posttraumatic stress.

Microsystem factors include interactions that the individual experiences and the subjective meanings ascribed to these interactions. The most salient microcosm or microsystem factor is usually the family unit, and the structure of the immediate family’s roles and interactions. It has been shown that some family structures may be more likely to produce perpetrators of violence against women. For example, family values of patriarchy and male dominance were shown to have a linear relationship with physical abuse of women (Heise, 1998). When applied to violence, the concept of the microsystem can be best described as the “immediate context of the abuse,” and situational or social factors surrounding the abuse (Heise, 1998).

Exosystem factors can be described as the formal and informal social structures that “impinge on the immediate settings in which a person is found and thereby influence, delimit or determine what goes on there” (Belsky, 1980, p. 321). Some exosystem factors have been linked to violence against women, such as poverty, low socioeconomic status, unemployment, and isolation of women and families (Belsky, 1980). Delinquent peer associations have impacts at the exosystem (social structure) and the microsystem (situational) level. It has been shown that males with sexually aggressive peers are more likely to report having raped or sexually coerced a woman (Heise, 1998).

Macrosystem factors may be described as a broad set of cultural values and beliefs that “permeate and inform the other three layers of the social ecology,” operating through their influence on the other levels (Heise, 1998, p. 277). Most feminist discourse on rape has focused on macrosystem factors such as patriarchy, but it is important to investigate, describe and discuss the impact of other factors (Heise, 1998). A nested, ecological approach acknowledges the important role of macrosystem factors without excluding the validity of contributions at the individual, situational, and social structural levels (Heise, 1998).

There are several macrosystem factors that have been linked to high levels of violence against women. Rigid gender roles have been linked to high incidences of rape in a culture or community; similarly low levels of rape are related to a lack of strongly defined gender roles (Heise, 1998). A sense of male entitlement or ownership of women is another predictor of high levels of violence against women. Also predictive of high levels of violence against women is the culture’s approval of physical punishment of women: in many societies it is perfectly accepted to hit a woman for minor to severe trespasses (which could range from forgetting a meal to adultery to being raped). Over time this normative physical assault can broaden the definition of what is considered acceptable violent behavior towards women (Heise, 1998).

Sexual violence on the scale of mass rape could not be explained without some accounting for the anger and hate directed against the women who are targeted for these attacks (Seifert, 1994). Theorists have asserted that rape of women by men is made possible by the undercurrent of anger, aggression, and hostility towards women that is part of the cultural landscape. Culturally ingrained hatred of or aggression toward women may allow for the possibility that individual men are able to enact the violence of rape (Seifert, 1994).

A cultural ethic of solving problems with violence also predisposes a society to high levels of violence against women, particularly sexual violence (Heise, 1998). The context and history of war can provide a cultural framework where the expected way to resolve conflicts involves violence or aggression, and civilian women become targets for sexual violence in accordance with this cultural principle of violent problem-solving.

Active war can be considered a time when the cultural value of violent problem-solving is most strongly enacted and reinforced. War is present at all levels of the ecological framework, and rape must be contextualized within the violent upheaval of war. Because the meaning and impact of sexual violence are highly dependent upon the social and cultural context in which the violence occurs, it is important to address the significance of wartime rapes (Seifert, 1994).

RAPE IN WAR

Winston Churchill said, “War is a game that is played with a smile,” and war can certainly be likened to a game with rules. These rules or norms of practice during wartime vary across time and place, but the soldiers’ prerogative to rape conquered women has traditionally been an accepted rule of war. To the victor go the spoils. Sexual domination of the “enemy’s women” is one of the benefits afforded to soldiers in battle. These rules dictate that the victor has “the right to exert violence against women… during campaigns of conquest or in the immediate post-war period” (Seifert, 1994). Ancient tests, such as the Iliad and the Old Testament, speak of rape in war. Even the terminology used to discuss sexuality, rape, and war belies the cultural connections between the concept of sexual violence against women and the concept of war: conquests are made in the bedroom and on the battlefield; military invasions may been described as “the rape of” Kuwait, Belgium, etc. (Seifert, 1994). “Rape, pillage, and burn” is a familiar phrase in the contemporary and historical vernacular (Brownmiller, 1994, p. 181).

It is often assumed that rape occurring in times of war is attributable to lawlessness or the wild abandon experienced by soldiers in combat, or the hard earned right of victors to sexually dominate the women of the conquered group. While it is undoubtedly true that some women are raped during war or ethnic conflict for non-strategic reasons, rape and sexual assault are intentionally utilized for military, territorial, social, or political gains. Sexual violence is employed as a tactic in violent conflict because of the physical and psychosocial effects on individuals, families, and communities (Copelon, 1994; Hardy, 2001; MacDonald, 2003; Swiss, 1993; Turshen, 2000).

Rape has always occurred in the wars of known history, and it continues to be a pressing problem in modern wars as its use has become widespread and systematic (Seifert, 1994). But modern women are more than just the spoils of war. Civilians are “the material war is waged with,” and women are considered “war material” to be used in a variety of strategic ways (Seifert, 1994). Many more civilians than soldiers perish in modern wars. “Those who do not carry arms are particularly vulnerable” in active warzones (Seifert, 1994). Women—who in wartime, make up the majority of the civilian population—are “tactical targets of particular significance” because of their role within the family and social structure (Seifert, 1994). Women are singled out as principle targets for the most effective destruction of a culture because of the centrality of their social roles in the family and community.

Wartime rape has been linked strongly to constructions of masculinity offered to soldiers and combatants. Social constructions of masculinity are essential to any discussion of sexual violence against women, and constructions of masculinity during wartime are particularly salient. Military service functions as a rite of passage for many young men, through which they attain an adult male status and identity. A military sociologist described how the values associated with the ideal of sexual virility in the exclusively masculine surroundings of the army become primary for the soldier’s conceptions of himself, as well as his social status (Seifert, 1994).

The social context also provides soldiers with norms that maintain perceived masculine status by the other soldiers (Seifert, 1994). These social values and ideals define the identity of soldiers, and create inner tensions because the soldier is constantly confronted with threats to masculinity (such as emotionality, empathy, horror, fear) and must preserve the construction of masculinity in the face of these “non-masculine” experiences. These cultural conceptions of masculinity as sexually aggressive may increase the likelihood of violence against women because of the normalizing of male dominance and aggression, and the desire to be accepted by other sexually aggressive males (Seifert, 1994).

Sexual violence contains attributes associated with hyper-masculinity (strength, power, forcefulness, domination, and toughness), so the act of rape may be considered a behavior that supports and validates this conception of masculinity. In some social groups, particularly in the context of war and ethnic conflict, rape can also function as a ritualized validation of a soldier’s male status and identity. The hyper-masculinized version of appropriate behavior for men links power and sexuality with violence, linkages that can have dangerous consequences for women who may be the targets of “masculine” displays of sexual violence and domination. Relating masculinity to dominance or toughness (usually important constructions of a soldier’s masculinity) is associated with cultures in which peacetime rape is prevalent (Heise, 1998). It stands to reason that this value of hyper-masculinity could become exaggerated during an active conflict and could increase perpetration of sexual violence against women.

Social pressure may function to spur on hyper-masculinized acts of sexual violence in an attempt to prove one’s manhood or attain the group’s esteem (Heise, 1998). Analysis of gang rapes provides further corroboration for the role of peer pressure and social norms of masculinity in the etiology of rape. The main purpose of gang rape appears to be proving one’s masculinity to the group through the display of sexual violence (Heise, 1998; Seifert, 1994). Attachment to other male peers who encourage abuse or violence against women is a predictive factor for males who abuse women sexually, physically, and psychologically (Heise, 1998). In this way, the macro system value of male dominance and the situational factor of peer pressure (among peers who have all been exposed to the same violent cultural construction of manhood) have a combined influence on the choices of individual men to participate in sexual violence. This provides a strong rationale for the concept that men rape during war because of peer pressure or social norms regarding violence against women, and sexual violence in particular is a way to demonstrate masculine power to the group.

In military conflicts, abuse of women is part of male communication: displays of machismo are enacted through sexual violence against women who are associated with the target males. The rape of women carries a man-to-man message, showing that the targeted men are not able to protect their women (Seifert, 1994). This male communication at the microsystem level is especially salient in cultures which consider women to be the property or social responsibility of their husbands or fathers (Heise, 1998). Men may interpret the sexual assault of “their” women as a direct attack on their manhood and their own integrity. In this way, “women are used as political pawns, as symbols of the potency of the men to whom they belong” (Cahill, 2001, p. 18).

Since “the purity of a woman’s sexual virtue is inextricably linked to the honor of her husband, father, and brothers,” a woman’s survival after being sexually penetrated by the enemy presents an affront to their manhood because the woman becomes a walking reminder of their failure (Hardy, 2001, p. 3). The threat to masculinity posed by rape of women associated with a man may be so severe that it motivates the man to seek revenge, or to turn his anger against the survivor or children born of rape. The crisis in masculinity conveyed through rape may be threatening enough to cause the men in the survivor’s life to isolate the her, cast her out, abuse her, or even murder her, because of the humiliation she represents.

MASS RAPE IN THE CONTEXT OF ETHNIC CONFLICT

During ethnic conflict, the meaning of rape is imbued with a deeper hue: rapes committed in war may aim to destroy the raped woman’s culture or community. Deconstruction of culture—and not necessarily the defeat of the army—can be considered one of the primary goals of rape warfare. Individual rapes translate into an assault on the community through the social emphasis placed on women's sexual virtue: the shame of the rape humiliates all those associated with the survivor. Combatants who rape in war often explicitly link their acts of sexual violence to this broader social degradation through their words and actions (Human Rights Watch, 1996).

When a woman is raped in the context of ethnic conflict and genocide, the symbolic message to the woman’s community is one of territorial conquest. The culture has been symbolically “penetrated” by the enemy, and this is evident in the physical penetration of the individual female representatives. The humiliation of a culture through systematic sexual destruction of the women is the primary goal of mass rape in ethnic conflict.

The female body “functions as a symbolic representation of the body politic [so] the violence inflicted on women is aimed at the physical and personal integrity of the group” (Seifert, 1994, p. 63). The “rape of the women in a community can be regarded as a rape of the body of that community,” and this symbolic assault is very much an intended consequence of genocidal rape (Seifert, 1994, pp. 64). It has been argued that men rape during war and genocide “because the acquisition of the female body means a piece of territory conquered” in symbolic terms (MacKinnnon, 1994, p. 84). Forced sexual penetration (especially when combined with ejaculation and insemination) announces conquest of the woman by the rapist, and by symbolic extension, dominance of the raping culture over the raped culture.

Mass rape in war draws upon existing gender dynamics and cultural factors to increase the damaging effects of the assault (Brownmiller, 1976; Dusauchoit, 2003). In patriarchal cultures, women are considered “symbols of the potency of the men to whom they belong” (Cahill, 2001, p. 18). The tactic of rape robs the husband of his control over his wife’s sexuality during the rape, but also robs him of the ability to sexually enjoy his wife afterwards because she may be injured, traumatized, or pregnant (Amnesty International, 2004). In this way, the male “is emasculated (and therefore dehumanized, rendered powerless) by being denied sole access to his woman” (Cahill, 2001, p. 18-9). This has been described as “the final symbolic expression of the humiliation of the male opponent” (Seifert, 1994, p. 59).

RAPE AS A WAR CRIME

Warfare “proper” is considered to be the confrontation that takes place between soldiers (Seifert, 1994). However, evidence shows that civilians suffer and die in wars to an extreme extent, often wildly outnumbering military deaths. These civilian deaths, while tragic, are not necessarily considered war crimes according to international law. ICTY Deputy Prosecutor Graham Blewitt clarified, “the mere fact that two armies or two parties to a conflict are killing each other is not a war crime: It is only when the parties step beyond the bounds of what is accepted. And modern-day armies are taught what constitutes the laws and customs of war” (Stover, 2005, p. 40).

A war crime is a punishable offense under international law that has been committed during wartime by a soldier or civilian. The 1899 and 1907 Hague Conventions began the establishment of these laws of war, but war crimes became firmly established in the War Crimes Tribunal at Nuermburg in 1945. The Genocide Convention of 1948 and the four Geneva Conventions of 1949 were integral to the development of these laws of war. The International Criminal Court refers to “grave breaches” of the Geneva Convention in its definition of war crimes, particularly the rights and appropriate treatment of civilians, injured soldiers, and prisoners of war.

These and other international treaties form the laws of war, which define what constitutes legal, illegal, and criminal acts. Perpetrating deliberate and unnecessary suffering for civilians may constitute a war crime, while acts that unintentionally harm or kill civilians may not be designated as criminal. The rights of noncombatants in wartime are particularly well outlined in the fourth Geneva Conventions (GCIV, 1949), which mandates humane treatment of all noncombatants. Civilians in wartime are protected by international law from murder, “mutilation, cruel treatment and torture,” and “outrages upon personal dignity, in particular humiliating and degrading treatment” (GCIV, 1949).

Rape may be considered a war crime because the perpetrator deprives the survivor/victim of her right to be treated humanely, and she is exposed to an extreme degree of humiliation, degradation and pain—which is against international law under the fourth Geneva Convention and other international treaties. At Nuremburg, the prosecutors did not deal directly with the issue of rape, although they did admit some evidence regarding sexual violence against women. The Tokyo Tribunal prosecuted rape, but it seemed to be more of an “afterthought” than an intrinsically important part of the judicial process (Stover, 2005). Sexual violence has been handled more directly by the International Criminal Tribunals for the Former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, where the war crime of rape has been prosecuted at the highest levels.

RAPE AS A CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY

The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court defines “crimes against humanity” as certain acts when “committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed at any civilian population” (ICC, 1999, Article 7). The acts include murder, torture, extermination, enslavement, deportation, forcible transfer, imprisonment or other severe deprivation of physical liberty, and other crimes. The Statute specifically lists rape, sexual slavery, forced pregnancy, enforced prostitution, enforced sterilization, and any other form of sexual violence of comparable gravity as crimes against humanity.

The term “crimes against humanity” was first introduced in the 1907 Hague Convention, and it appeared in the record again eight years later when the Allies accused the Ottoman Empire of crimes against humanity (Stover, 2005). It was not explicitly linked to sexual violence. Later the concept was once again utilized (this time as a basis for levying charges against the Nazis at the Nuremburg trials) again without directly referencing rape as a crime against humanity (Stover, 2005).

The International Criminal Tribunal on Yugoslavia (ICTY) was the first time that rape had been charged as a crime against humanity. The prosecution argued that witness testimony established that a crime against humanity was committed in Foca, including a “widespread or systematic pattern of sexual assaults” (Hagan, 2003, p. 190). The rape trials at the ICTY presented evidence of “an organized campaign of rape and sexual assault upon various women at various locations over a prolonged period of time” (Kunarac transcripts, p. 332, as cited in Hagan, 2003, p. 183). At the trials, there was also discussion of the “policy of ethnic cleansing unleashed by the Bosnian Serb leadership on the non-Serb population,” of which mass rape was an essential strategy (Kunarac transcripts, p. 303, as cited in Hagan, 2003, p. 183). Human Rights Watch (2005) has declared the sexual violence to be “a fundamental violation of human rights,” and has further stated that “acts of sexual violence committed as part of widespread or systematic attacks against a civilian population in Darfur can be classified as crimes against humanity” (para. 12).

RAPE AS AN ACT OF GENOCIDE

While rape may seem antithetical to genocide, it is often a cornerstone of these brutal campaigns because of the devastating effects on women, families, and communities. Genocide was defined by the United Nations as “acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group” (UN, 1948, Article II). These acts may include killing, causing serious bodily or mental harm, deliberately inflicting conditions of life calculated to bring about the group’s physical destruction, imposing measures intended to prevent births, or forcibly removing children from the group (UN, 1948, Article II). Rape is a forced sexual penetration that can cause death, serious bodily and mental harm, bring about physical destruction of the group, and can impede births. Thus rape can be considered an act of genocide and it has been recognized as such by international criminal courts.

Mass rape is a strategy of genocide because it is a condition calculated to bring about physical destruction of the group. Mass rape prevents births within the target group through damage to reproductive capacities or social fitness of women. In-group births may be prevented through forced impregnation. Children born of rape are seen by the mother’s community as a soiling the group’s bloodlines, while the perpetrators may consider the woman and the child to have been “ethnically cleansed” through the assault (MacKinnon, 1994, p. 191). Many communities believe that the survivor has been penetrated and thus tainted by “the enemy:” the child born of rape is generally considered an enemy or a pariah in the community.

Rape and sexual violence may be particularly destructive when they occur within the context of ethnic cleansing or genocide, and it is necessary to attend to factors that amplify the significance ascribed to these acts. Rape can be a strategy of war, ethnic cleansing, and genocide because it reduces the civilian population through a variety of practical means while instilling fear, submission, compliance, and fleeing from areas of contested territory (International, 2005; MacKinnon, 1994). Survivors, family members, and witnesses tend to avoid traumatic reminders such as the location of the rape (International, 2005; Zalihic-Kaurin, 1994). Brutal and public rapes remove the desire to return to the areas where the traumatic events took place for large numbers of people at once. When rapes are committed in a widespread and systematic fashion, these assaults on women come to represent an assault on the community (MacDonald, 2003). Mass rapes “reverberate through the decades and across the borders and have a lasting effect on the position, identity, and self of women” (Seifert, 1994).

Médicins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) describe rape as a “weapon used to destabilize or even break a particular ethnic, national, or religious group or to ‘ethnically cleanse’ a whole society” (Dusauchoit, 2003, p. 3). In the context of ethnic cleansing and genocide, the trauma of rape may be intentionally maximized by the perpetrator(s) to cause damage or death, and to send a message. Physical abuse or torture, repeated assaults or gang rapes over a span of time from days to weeks, forced pregnancy and childbirth, the combination of rape with murder or torture of the survivor’s loved ones, public humiliation of the survivor and her family, and verbal abuse of the survivor and her community contribute to the devastation (Kozaric-Kovacic, 1995a; Turshen, 2000). Mass rapes are combined with organized slaughter, looting, burning, pillaging, and starvation for exponential impact (Fischman, 1996; Frljak, 1997; Swiss, 1993).

After the rulings of the International Tribunal on the former Yugoslavia, Patricia Sellers (the legal advisor for gender-related crimes) stated “now we can say rape is a crime, a crime against humanity, or a war crime, a constituent part of genocide” (as quoted in Hagan, 2003, p. 201). These landmark rulings paved the way for future perpetrators of genocidal rape to be held accountable for their actions.

About Me

- Ruby Reid, MSW

- I am currently pursuing a PhD in Social Welfare at Berkeley, concentrating in local, national and international responses to large-scale disasters, wars, and genocide. To me, social work is not a job. It is a way of life, a faith, and a daily practice. My mother is a social worker and I was instilled with social work values as a young child. I carry those values of respect and compassion for other human beings, the importance of service and integrity, and these values lead me to endorse Barack Obama for President of the United States. Barack Obama represents a new and positive vision for the future of America. He is honest, hard-working, and unafraid to face the nuanced and complex problems of our country and our interconnected world. I am proud to support a candidate who will truly bring change for the American people and for all members of the world community.

Upcoming Research Project

Interviews will be conducted with women who survived the wars in Croatia and Bosnia-Hercegovina during the 1990s. These interviews will focus on how the experiences they had during the wars may have impacted their lives.

I will be traveling to the region to meet with collaborators and advisers on the project from May 15-June 15 2007.

Would you like to learn more about my trip this summer?

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

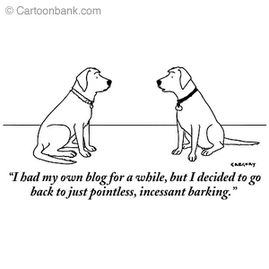

Hopefully it's not all totally pointless...

No comments:

Post a Comment